Old children’s TV mainstay Monkey, aka Monkey Magic, recently dropped on Netflix, exposing a whole new generation to martial arts action, Chinese myth, Buddhist philosophy, and some jokes and stereotypes that don’t pass muster anymore. Film critic at large Travis Johnson reports in.

If you were a kid in Australia any time from the late ‘70s to the mid-’90s or thereabouts, you almost certainly saw Monkey.

Originally broadcast on Japan’s Nippon TV from 1978 to 1980, Saiyūki, as it was titled in Japanese, was adapted from the book Journey to the West by Wu Cheng’en, one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature. But banish all thoughts of highfalutin, impenetrable philosophising – Monkey was full of high-kicking, accessible philosophising, cramming the book into an “adventure of the week” serial format.

In the worlds before Monkey, primal chaos reigned…

The title character, played by Masaaki Sakai, is the mischievous and arrogant King of the Monkeys. Imprisoned for offending Heaven, as penance, he is tasked with accompanying the boy priest Tripitaka (Masako Natsume) on a perilous journey from China to India to retrieve a batch of Buddhist scriptures.

Also along for the ride are two former Officers of Heaven who have been transformed into monsters for their own crimes: the gluttonous, lecherous pig monster Pigsy (Toshiyuki Nishida, then Tonpei Hidari in Season 2), and the cannibal river monster Sandy (Shiro Kishibe), plus a dragon (Shunji Fujimura) who transforms into a horse for Tripitaka to ride.

And that’s your lot! Every episode, Monkey and the gang would come across some weird problem they’d have to solve, often a town plagued by some kind of demon or monster, which they’d deal with by employing a winning combination of martial arts and Buddhist/Taoist philosophy. There was plenty of action wrapped around a cool moral lesson and, thanks to seemingly endless afternoon reruns on the ABC, generations of Aussie kids got a crash course in Eastern philosophy in between Danger Mouse and Doctor Who.

It’s impossible to overstate how popular Monkey was. As a little sprog in the early ‘80s, I couldn’t tell you how much playground time was devoted to running around hitting each other with broom handles (Monkey and co mainly fought with staves, which was convenient for kids with easy access to Mum’s broom closet) and imitating Monkey’s screech of pain whenever Tripitaka sicced the headache sutra on him. If I have to explain every little element of the show we’ll be here all day – just know that it’s a heady mix of Buddhism, Taoism and Chinese folklore, with a surprisingly witty script, topped and tailed by some bangin’ jams from Japanese pop band Godiego:

Ah man, it’s great – just hearing that puts me back in my dressing gown whacking other kids upside the head with a stick. So, when I discovered Monkey had suddenly appeared, fanfare free, on Netflix, I was a pretty happy middle-aged man all set to relive his childhood (I normally side-eye unchecked nostalgia, but this is Monkey we’re talking about). Even better, this was the whole two seasons – back in the day only half of the second season was dubbed into English and broadcast, but in 2004 the remaining 13 episodes were dubbed by the original English language cast and released on video (Google it) and DVD. So, I queued it up, settled on my couch, and started my own little Journey to the West.

And it still rules! I still love it…mostly. But the thing about the stuff we loved back in the day is that it stays the same while we and our culture continue to grow and develop. So, Monkey comes with some caveats these days, and they’re worth talking about.

Dubbing dramas

Look, I’m just gonna come out and say it, and you can drag me for it in the comments: in the cold light of 2021, the English dub is pretty racist.

Monkey was dubbed into English in the UK in 1979 with a script translated by David Weir (he also translated The Water Margin, another Japanese series based on Chinese literature – the guy knew his wheelhouse). It’s a fantastic translation and is really well performed by the voice cast, which includes David Collings (Monkey), Maria Warburg (Tripitaka), Peter Woodthorpe (Pigsy), Gareth Armstrong (Sandy), Fawlty Towers’ Andrew Sachs (the dragon-turned-horse), and among others, recent migrant to Australia, Miriam Margolyes, as a number of minor characters. Each character is distinctive and the script, rather than a direct-ish translation, is crafted with care, incorporating a lot of jokes, puns, and wordplay that more or less match the mouth movements onscreen. It’s rather brilliant.

And everyone is doing their voicework in a horribly stereotyped “Oriental” accent.

I defy anyone to close their eyes, listen to the vocal track divorced of the action of the show or their own fond memories, and not flinch at least a little. It’s some real Mickey-Rooney-in-Breakfast-at-Tiffany’s stuff. Really thick quasi-East-Asian accents and phrasing, designed to present a parochial Western idea of what the exotic, mythical Far East sounds like. It’s actually cringe-worthy.

The standard response is that the series is a product of its time, and that’s maybe fair enough, but don’t forget the more recent voiceover work was done in 2004. Is it offensive? Me, personally, I’m hard to offend (the shit I’ve seen, folks…) but I’ll say that I find it uncomfortable. Not for my own enjoyment (let me say it again – I adore this series), but I find it hard to recommend to newbies without laying out some caveats. You don’t even have the option of watching it in the original Japanese with subtitles if the voice work is a real turn-off – the only audio track is English.

And here’s the thorny part – I don’t even want the voices changed. To me, that’s what Monkey and Sandy and Pigsy sound like, and they’ve sounded that way since I was four. For me, this show is one of those core, formative texts, one that’s informed a lot of my sensibilities and tastes. But I’d be lying if I said that looking at it now didn’t put me on the horns of a dilemma.

And hell, we haven’t even gotten to some of the problematic dialogue, such as when Monkey called a tiger demon a homophobic slur…

Maybe Netflix needs a #problematic category?

I’m only half-joking. I’m staunchly anti-censorship. In my (white, straight, cis) opinion, pulling the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons episode of Community was a ridiculous overreaction, covering Daryl Hannah’s ass with CGI hair was a crime against art, and I want to watch Song of the South. Hell, I want to watch the non-Special Edition versions of the original Star Wars trilogy. Not just because I’m a fan, but because I’m a film scholar, and when access to films or TV series is removed, we lose a little piece of history, a little bit of culture.

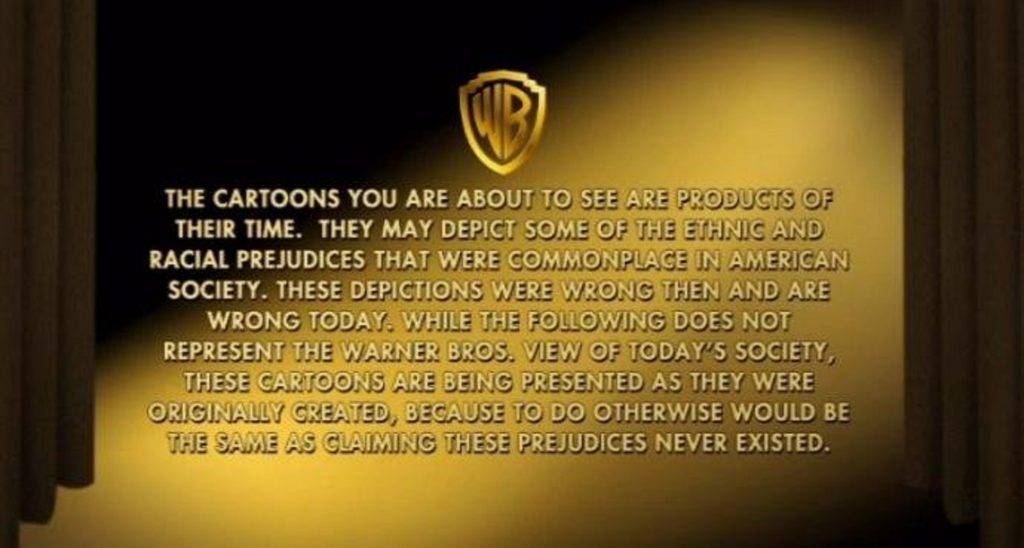

Yet while I’m anti-censorship, I’m pro-information, in that I think people need to be equipped with enough data to decide if they want to expose themselves to certain stimuli, certain works. Spoilers be damned (and spoiler culture as a whole can go jump as far as I’m concerned), a lot of work from the past needs to be put in its proper context for modern audiences to decide if they want to dip a toe in. That means classification ratings, content (not trigger) warnings, and the like. Disney has taken a stab at this for stuff like Dumbo, but still keeps works they consider a bridge too far, like the aforementioned Song of the South, in the vault. Warner Bros. has done well in this regard, heading some of their more poorly-aged cartoons with an explanatory note, although some remain out of circulation.

Netflix? Not so much, although there have been calls for them to do so. Maybe they should. Is there a good reason they shouldn’t?

I’m using Monkey here as a specific example, but what we’re talking about is an ongoing process. As society evolves and changes, older works are going to be found wanting, and to decry any criticism of a cherished film or series as censorship or “triggered” is weak sauce – we need to grapple with how to frame older works of value that contain elements that fall short of our current standards. Here’s a whole essay on the matter.

But there’s no one-size-fits-all approach that will suit every work and every audience, every issue. If we imagine a scale with censorship and withdrawal on one end and open slather on the other, culturally we’re mired in the middle, arguing over inches. Which is fine, by the way; culture is a conversation, and we negotiate its meaning every day. Finding fault with previously hallowed art isn’t a sign of regression, it’s a sign that as a culture we’re becoming more complex, nuanced, and empathetic, and that’s a good thing.

In the meantime, I highly recommend checking out Monkey on Netflix. It’s a great show…but, you know, there are some caveats.